of burden carried

the load for native

peoples of the

high-altitude

Altiplano in South

America, and they

continue to do so

today. On the

other side of the

globe, dromedary

and Bactrian

camels performed

the same tasks,

trekking the

deserts of Asia

and the Middle

East in long

caravans, a vital

part of commerce

for centuries.

The alpaca is not a transporter,

though the alpaca is a clothier. Despite

the fuzzy, cute image of the huacaya

breed alpaca, or the graceful elegance

of the suri breed, these alpacas are every

bit as “tough” on the inside when it

comes to survival. Alpacas are born of

sturdy stock, and though not bred for

a strong back, they ask no more from

the planet than the llama or camel.

Few know that the alpaca/ llama/camel

prehistoric precursor “camel” orginated

in North America. The alpacas’ return

is a bit of a homecoming.

When the Spanish arrived in South

America, they brought with them many

merino sheep. We know the impact the

Conquistadores had on the original

South American human inhabitants,

but many don’t realize the deliterious

impact made by the arrival of the sheep.

For centuries, the alpaca provided

indigenous people with a wonderful,

functional source of cloth. Cave

drawings in Peru, dating back 5,000

years, show carefully depicted drawings

of llamas and alpacas. History finds

the alpaca highly prized and pastured

on the best of the best coastal land.

Alpacas were actually considered cur-

rency by royalty. That all ended when

the Spanish arrived and made room

for their sheep. The alpacas of the lush

lowlands were slaughtered, forcing

survivors to relocate to the remoteness

of the steep, arid Andes mountains.

Being of sturdy camelid stock, how-

ever, the alpaca made the retreat to the

high Altiplano, where they adapted and

survived. They lived at altitudes only

exceeded on Earth in the Himalayas.

They grazed in a dry, harsh, cold land

that yielded little more to eat than

scant patches of native grasses. The

vast majority of the world’s alpacas

remain there today.

With the merino invasion, and alpaca

exile to the Andes, something was gained

and something was lost. The alpaca

adapted to its circumstances, and herd

sizes regrew, but the quality of fiber fine-

ness eroded. Analysis done on the fine-

ness of ancient alpaca garments entombed

with royalty revealed micron counts on

the cloth fibers that

are much lower

than most alpaca

being produced

today. That the

post-Spanish alpaca

adapted for sur-

vival is clear, but

not clear is what

happened to the

fineness. Perhaps

the finer-fibered

stock was slaugh-

tered, did not

adapt as well,

or that ancient

husbandry skills

were lost. Today,

through modern

selective breeding,

we are returning this lost fineness with

each successive generation.

For centuries, it was not legal to

export alpacas out of Peru. In the

mid-1980s, however, pragmatic

government agencies relented and

allowed alpaca exportation to begin –

starting first in Chile and Bolivia,

then later in Peru. The bulk of

migrating alpacas went to North

America and Australia. Herds on

those two continents now number

over 150,000 head.

The main food alpacas consume

is grass or hay, and not much of it –

approximately two pounds per 125

pounds of body weight per day. As a

general rule, alpacas need only 1.5% of

the animal’s body weight daily in hay or

fresh pasture. A single, 60-pound bale

of hay, for example, can usually feed a

group of about 20 alpacas for one day.

Grass hay is best, while alfalfa should

be fed only sparingly, due to its overly-

rich protein content. Alpacas are pseudo-

ruminants, with a single stomach divided

into three compart-ments. They produce

rumen and chew cud, thus they are able

to process this modest amount of food

very efficiently.

58

Alpacas

Magazine

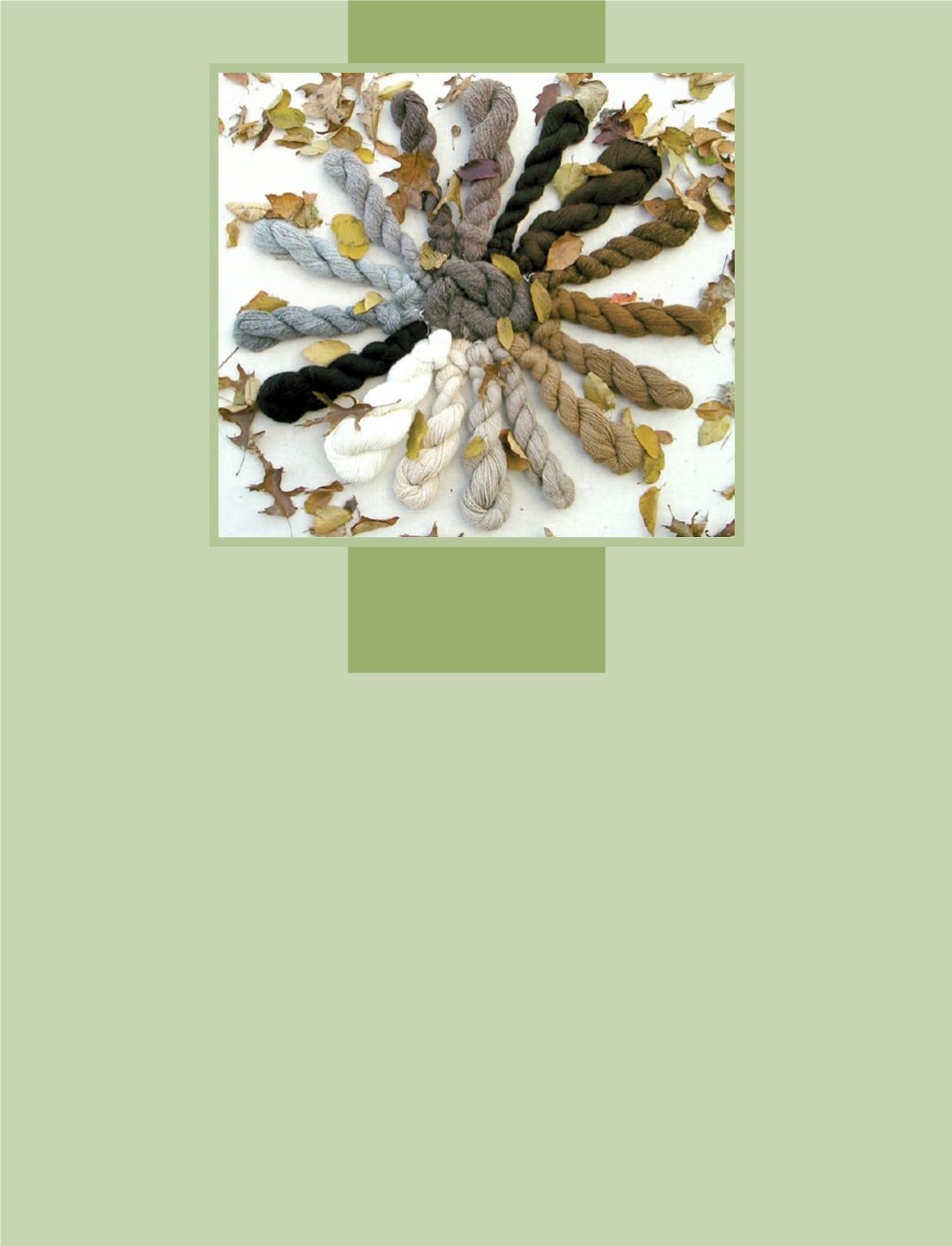

It may seem almost counterintuitive

that wearing something luxurious

as an alpaca garment can also be

earth-friendly, but it’s true.

© 2009 Ed Kinser