24

|

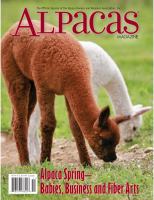

ALPACAS

MAGAZINE

NATURAL FIBER

Industry News

History

In 1789 Count Buffon, the French naturalist

and author, published his work, “Natural

History,” in which he drew attention to

the lack of information about the South

American camelids—in particular the

alpaca and the llama. Buffon wrote:

“It is very noticeable that the domes-

tic animals of Peru and Chile, unlike the

horses in Europe or the camels in Arabia,

are hardly known and this after more than

two centuries of Spanish rule. Not one

author has given an accurate description

of the daily use of these animals in their

region—all they say is that they cannot

be transported to Europe nor taken away

from the mountains. The writers living in

Lima could, at the very least, have drawn,

described or dissected them.”

Indeed, Buffon rectified his own com-

plaint by publishing one of the first scien-

tific drawings of a llama that we have.

However, and despite what Count Buffon

was told, there is evidence that at least one

live llama was exported to the Netherlands

as early as 1558 when the species was

referred to as

Allocamellus.

Today it is

classified as

Lama glama.

Essentially domesticated around 7,000

years ago as a pack animal, the llama is

strong, hardy and was well-equipped to

make the long and arduous treks from

Bolivia, travelling over the Andes and

down to the coastal regions of Peru and

Chile. In Incan times, the animals accom-

panied the army, carrying provisions and

were also a source of meat. In religious

ceremonies they were often sacrificed in

the belief that they could help man see

into the future.

A traditional way of life

These days the majority of the world’s

llama population is to be found in Bolivia

where around 950,000 animals produce an

average 1.9 million kilograms of fiber per

annum. Bolivia’s leading processor

of fiber through to finished garments is

Altifibers S.A., based in La Paz. Peru is the

next largest producer, with approximately

350,000 llamas.

There are two distinct breeds of llama—

the Kcara (or light fleece), which is most

commonly used as a beast of burden, and

the Chaku (or heavy fleece) which is the

main source of llama hair for textiles.

The animals survive on any type of

pasture and can, in fact, go several days

without eating. They can tolerate thirst for

a considerable period of time.

An ancient and traditional way of life is

still carried out by some of the ‘llameros’

(llama herdsmen) who live high up in the

Altiplano Region of the Andes, some 4,600

meters above sea level, and who every

morning leave their small stone houses

with thatched roofs to let their llamas out

of the pens where they have been corralled

for the night. Once freed, the llamas head

out to graze the dry pasturelands at the

top of the mountains.

From November to March, during the

rainy season, the llameros are intent on

ensuring that the most virile ‘jaynachos’

mate with as many of the females as

possible, as the breeding season is

relatively short. This is also the time

when the animals are sheared.

In April some of the herds are rounded-

up and descend to the fertile valleys,

following the routes of their ancestors.

With each animal carrying a load of

30 kilograms, they pass through villages

and settlements on the way, with their

merchandise of clay pots, dried meat

(‘charki’), textiles, ropes and guano (used

as a fertilizer) which will be traded for

corn, beans, potatoes and barley. At each

settlement the llamas will also be used to

carry the crops in from the fields.

When the harvest is safely gathered-in,

the herds move on to the warmer desert

plains where further trading will take

place for red peppers, kidney beans,

figs and dried fruits.

It is in the desert that the llameros

practice their ancient rituals to give thanks

for the first leg of their journey and to ask

for luck to complete the final trek down

to the sea. With this in mind some of the

animals will be sacrificed and their blood

used to paint symbols on stones.

Inkarri legend tells that “… when the Inca

distributed resources while descending

from the Altiplano, he gave only livestock

and grazing grounds to the inhabitants of

Sibaya (the Andes) and, since that land

could not be cultivated, he gave them

fields in the sea where they could grow

a seaweed called ‘cochayuyo’.”

At the coast, other foods are loaded for

the herd’s return to the Altiplano—fish,

rice, sugar cane and fruit and, when

September comes, they head back. Some

llameros may deviate their homeward

route to spend more time along the coast

visiting Mamacocha (the Sea Mother,

goddess of water) before ascending to the

mountains—their journeys are long and

tortuous and in an area that can cover

the whole of Tahuantinsuyo (the Inca

Empire which stretched from Colombia

to Northern Argentina).

Llama Fiber:

Moving Out of the Shadows

BY FRANCIS RAINSFORD

Llamas in the Andean Altiplano.

Photocourtesyoftheauthor