DNA Testing for Meningeal Worm in Camelids

Q & A Session with The Ohio State University’s Meningeal Worm Investigation Team

The Alpaca Research Foundation, in collaboration with the Greater Appalachian Llama and Alpaca Association, provided funding support to a team of investigators at the Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine. The team includes members from three departments: Veterinary Clinical Sciences, Veterinary Biosciences, and Veterinary Preventive Medicine—all based at the Veterinary Medical Center and engaged in camelid medicine.

Dr. Jeffrey Lakritz has long led camelid-related research, clinical medicine, and dissemination of information to owners. Dr. Laurie Milward, a Clinical Pathologist, complements Dr. Antoinette Marsh, whose expertise in molecular and immunoparasitology supports applied clinical diagnostic investigations. The following questions provide an update on their project through a question-and-answer article. The team from left to right is Antoinette Marsh, Jeff Lakritz, and Laurie Milward.

What is the “meningeal worm” in camelids?

The meningeal worm, Parelaphostrongylus tenuis (P. tenuis), is a neurotropic nematode with a tendency to migrate to the brain cavity as part of its life cycle. In its natural host, the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), the parasite causes little to no disease. Adult worms live in the deer’s meninges and produce larvae (L1) that are shed in feces. Terrestrial snails and slugs serve as intermediate hosts, where the larvae develop to the infective stage (L3).

Camelids, along with goats, sheep, cattle, and horses, are aberrant hosts (not the natural host). They acquire the infection indirectly by grazing on forage contaminated with infected snails or slugs. After ingestion, L3 larvae migrate into the spinal cord and brain tissue, causing severe neurological and sometimes ocular disease. Because camelids are highly sensitive to this migration, even a small parasite load can result in clinical illness. In contrast, the parasite and white-tailed deer have co-evolved, allowing deer to carry the worm without significant harm.

Ohio pasture grass in July with slugs (intermediate host of P. tenuis) congregating at the base of a wooden fence post.

What disease does it cause in camelids?

In camelids, P. tenuis can cause neurological disease ranging from no apparent signs to severe, life-threatening illness. Affected animals may show incoordination, weakness in the limbs (especially the hind legs), difficulty standing, or may become completely recumbent.

What other things mimic the P. tenuis clinical signs seen in camelids?

Several other conditions can exhibit signs similar to those caused by P. tenuis. Infectious agents that produce inflammatory lesions in the central nervous system (CNS) or spinal cord may appear similar, including protozoa, viruses such as herpes, West Nile, and rabies, bacteria like Listeria, and fungal organisms. Metabolic disorders such as polioencephalomalacia from thiamine deficiency (sometimes linked to inappropriate drug use) or sulfur toxicosis can also cause neurological symptoms. Tick paralysis and tick-borne diseases may present with comparable paralysis or neurological disease. Finally, spinal cord injury, or age-related changes that compress or inflame the cord, can be mistaken for P. tenuis.

What is your team doing to help distinguish P. tenuis from other agents that cause neurological disease in camelids?

We are developing a DNA-based test to find P. tenuis DNA in cerebrospinal fluid. This approach is similar to methods used in human medicine—identifying small amounts of parasite DNA and linking it to clinical signs observed in the camelid. Other diagnostic methods can only suggest the presence of a helminth in the CNS. For example, the detection of eosinophils infiltrating the CNS indicates a parasitic response but does not confirm P. tenuis specifically. Instead, veterinarians interpret this finding in the context of additional evidence such as history, age, season, and exclusion of other causes. Even so, cytology remains a valuable diagnostic tool, and sample collection may also provide therapeutic benefits.

How is the DNA test different than an antibody-based test?

Antibody tests are an indirect method, and currently, there are none available for P. tenuis early infections in camelids. Some investigational studies have measured camelid antibody responses to better understand how the parasite enters, survives, and causes disease. However, interpretation is limited: if the integrity of the CNS is disrupted, systemic antibodies may leak into the CNS and confound results. By contrast, detection of the worm’s DNA provides direct evidence of parasite presence and is more closely associated with the clinical signs observed in affected camelids. Our approach draws on methods and findings from human medicine, particularly studies of Angiostrongylus cantonesis (rat lungworm, A. cantonesis), a parasite found in the southeastern United States, Hawaii, and the Caribbean. Rat lungworm causes eosinophilic meningitis and other severe CNS disorders in humans and dogs, which closely parallel the presentation and biology of meningeal worm infection in camelids.

What is the standard of care for camelids with meningeal worm?

Early diagnosis is critical, as it allows the veterinarian to begin treatment promptly. Standard care generally includes:

- Reducing inflammation with corticosteroids or steroid-like drugs.

- Administering anthelmintics such as fenbendazole.

- Providing supportive care and physical therapy to maintain mobility and strength.

- Relieving cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure by carefully removing fluid, based on the animal’s size and the degree of spinal cord compression. In human cases of A. cantonensis, similar CSF removal has been shown to ease symptoms.

Collected CSF can be analyzed in a veterinary diagnostic laboratory. The presence of numerous eosinophils, combined with compatible clinical signs and the absence of other cell types, supports a presumptive diagnosis of meningeal worm. DNA detection, however, provides direct evidence of P. tenuis in the CNS, confirming that the parasite is causing nerve and tissue damage. This allows veterinarians to target both the worm and the associated inflammatory response more precisely.

Because CNS disease is very difficult to diagnose to a specific etiology (parasite, virus, bacteria, nutritional deficiency, or trauma), veterinarians may also employ additional diagnostic tools—such as imaging or clinical pathology—to strengthen the diagnosis and guide appropriate treatment.

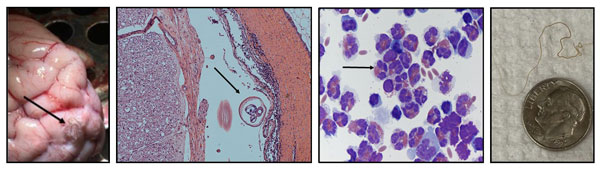

Above, from left to right: P. tenuis worm on the surface of the brain, cross-section of a worm within the CNS, cells harvested from the cerebrospinal fluid with many eosinophils present as evident with their internal granules, and tissue excised adult worm with a dime for size comparison.

What has been the most surprising part of this investigation?

As part of the specificity evaluation for the DNA test, other potential or related parasites were needed. When we reached out to colleagues, Dr. Heather Walden (University of Florida) for A. cantonesis, Dr. Christian Leutenegger (Antech Diagnostics) for Paralephostrongylus andersoni, and Dr. Richard Gerhold (University of Tennessee) for additional P. tenuis controls, they readily provided materials. These contributions have been invaluable in strengthening confidence in the assay’s specificity. In addition, the team at Ohio State University Veterinary Medical Center Hospital for Farm Animals, including new faculty member Dr. Michelle Carman, is actively seeking case material to further validate the test and provide consultation on complex neurological cases. It really takes a multi-disciplinary team with additional collaborators to address this challenging parasite.

What has been the most difficult part of the work?

Obtaining what is considered “gold standard” samples, meaning the animal has a definitive diagnosis (worm seen in the CNS) and both CSF and blood are available for analysis. These samples are essential for validating the DNA test and establishing its specificity, sensitivity, and predictive values, which in turn guide veterinarians in understanding how reliable the test is for diagnosing disease. The Hospital for Farm Animals sees a number of ataxic camelids, but not all are due to meningeal worm. As discussed earlier, other etiological agents can cause neurological diseases, and in some cases, no definitive diagnosis is made. Yet, with early intervention and supportive care based on a presumptive P. tenuis diagnosis, animals often recover, even if the parasite was not the cause of the problem. The important component is that the camelid successfully returned home with its owner.

Can veterinarians send in samples for DNA testing for P. tenuis?

Yes. There is a tendency for increasing presumptive P. tenuis cases during the late fall and winter. For additional information on submitting samples, our group can be contacted through the project principal investigator's email address, Marsh.2061@osu.edu.

Where did the support come from to pursue this research?

There is a definitive need in the industry and livestock health for improved diagnosis of this parasite. The funding came from the Alpaca Research Foundation and the Greater Appalachian Llama and Alpaca Association through a competitive application.

Is this work like other clinical investigations your team has pursued?

Yes. It is very similar to Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis (EPM) diagnosis and clinical biology work. Dealing with neurological disease diagnosis is an incredibly difficult and complex area. Meningeal worm is even more difficult because in vitro cultivation of the life stages is not possible, nor is there a laboratory model of disease to dissect out the immunological processes and validate a diagnostic test. P. tenuis is a much more difficult parasite to work with in the laboratory and clinical setting.

Are there other emerging parasites that camelid owners should be aware of?

Yes, recently, the Haemaphysalis longicornis (Asian longhorned tick) has been making its way across the eastern side of the United States and has been detected in Iowa. As this tick is newly introduced to the United States, all of the pathogens this tick may transmit are not fully understood. This tick replicates by parthenogenesis (females need not mate to produce offspring, resulting in reproductive advantages over other ticks). It is important not to introduce or establish this tick in your pastures. This tick will feed on a variety of mammals. Recently, besides being found on cattle in northern Ohio, it was found on horses passing through an auction. Therefore, it is very likely that this tick will use camelids as a host too.